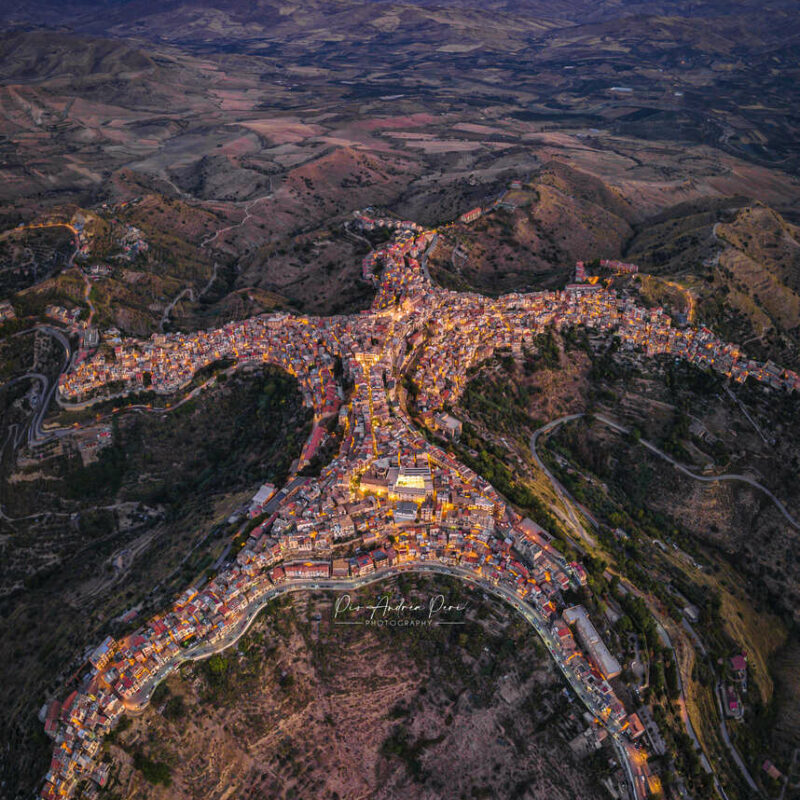

The ancient charm of Centuripe, the geoglyph town

Among the countless beauties that our country can boast, there is undoubtedly a village in Sicily that, seen from above, resembles a reclining person, or according to others, a starfish, and which resembles in miniature the mysterious geoglyphs of Nazca and Palpa in Peru. It is Centuripe, a picturesque village with ancient roots, in the province of Enna, perched atop a mountain formation at 733 meters above sea level, not far from the suggestive Cannizzola Calanchi, from which you can admire the western slope of Mount Etna, the Simeto valley, and even the Catania Plain, which is why Garibaldi appropriately called it “the balcony of Sicily” during the famous Expedition of the Thousand. Unlike the mysterious Peruvian lines, Centuripe owes its peculiar shape to the polylobate planimetric development that the inhabited center has undergone over the centuries, now unmistakable for its row houses on multiple floors crossed by characteristic stepped alleys that overlook the valley below.

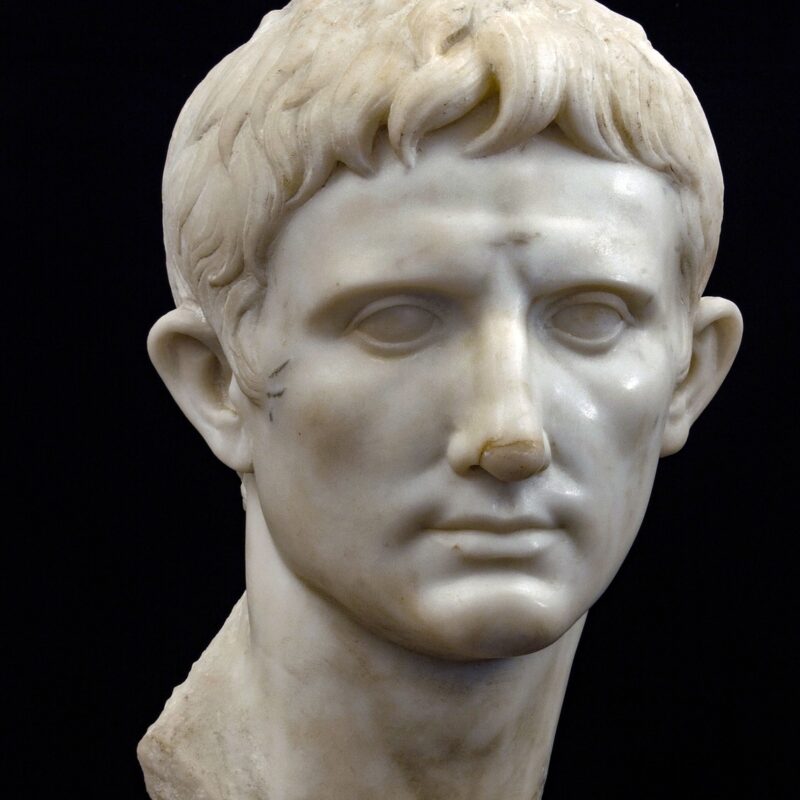

Having clarified the mystery of its unique appearance, the small Sicilian town will not fail to amaze even the most seasoned and curious travelers with the charm of its millennia-old history. The origins of Centuripe (Centuorbi in the local dialect) are lost in the mists of time; the area where the municipality currently stands was already inhabited in prehistory, as evidenced by the important Neolithic rock paintings discovered in the “Riparo Cassataro,” currently unique in eastern Sicily. Colonized in the 7th century BC by the Siculi, a population of Oscan-Umbrian origin, as documented by the important askos (a drinking vessel) found during an excavation campaign, now preserved in the Regional Museum of Karlsruhe, which bears the longest inscription in Sicilian that has come down to us, Centuripe certainly experienced its period of greatest splendor in the Hellenistic and then Roman ages, becoming one of the most important centers of coroplastic and ceramic production in the eastern Mediterranean basin.

Starting from the 3rd century BC, the local terracotta industry reached such a degree of refinement in the production of terracotta votive statuettes as to deserve the epithet of “Tanagra of Sicily,” named after the famous city of Boeotia, famous for its coroplastic tradition. Some of these finely crafted Tanagra figurines depicting Aphrodite, flying Erotes, dancing Fauns, and Psychai, are now preserved in the local Archaeological Museum, one of the most appreciated destinations for visitors due to the richness of the preserved artifacts. Among these stand out the amphorae with characteristic decorations in relief floral or architectural painted in tempera with rich nuances, often recalling the Dionysian cult, or the vases in the form of large heads or colored busts with reddish tints and embellished with refined shading. Models of beauty known to experts as “centuripine vases,” according to historians, there would be as many as 39 autochthonous types, which according to experts influenced the production of other Sicilian workshops in the classical age; some excellent examples of this tradition can now be admired at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Despite the looting of the archaeological heritage over the centuries, the great Centuripe tradition continues to thrive in the small ceramic industries and workshops where high-quality copies of ancient vases are reproduced, much appreciated by tourists. Important vestiges of the glorious past are also preserved in the historic center, such as the Hellenistic-Roman structures with “ancient rooms,” near the Church of the Crucifix and the cistern fountain of the Roman Imperial era known as Dogana, just 500 meters from the Museum. Outside the city perimeter, there are surely interesting remains such as the Hellenistic-Roman thermal baths in the Acqua Amara area and near the Sorgiva Bagni, and also the Iron Age necropolis, with stone circle tombs in Contrada Casino, the ruins of an ancient settlement with an annexed necropolis dating back to the 8th century BC in the Vallone Gelso area, the monumental complex of the ancient seat of the “Augustales” near the Barbagallo Mill, the ruins of what is commonly known as the Roman Bridge, near the Barca di Biancavilla Bridge, an important testimony to the strategic position that Centuripe occupied in Roman times along the wheat road that connected Catania with the Tyrrhenian coast, going up the Simeto river course, passing through Aetna (Paternò), Centuripe, Agyrium (Agira), Assorum (Assoro), Henna (Enna), and continuing up to Terme Imeree. But Centuripe is not only classical antiquity; the small center is adorned with places of worship of particular beauty such as the colorful Mother Church dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, dating back to the 17th century, and the Church of the Crucifix that embellish its maze of alleys.

A particularly heartfelt devotion manifested in the suggestive celebrations on the occasion of the feast days of the patron saints Santa Rosalia and San Prospero (September 15-19), as strong as the attachment to rural traditions that are alive today in the collection of Cultural Anthropology of the Ethno-Antropological Museum of Peasant Civilization, housed in the former Municipal Slaughterhouse, which collects objects from pre-industrial daily life. Of course, there are also attractions for gourmets who can delight their palates with genuine local products, including the prized saffron, excellent local cheese, and delicious cold cuts, but also with the delicacies of typical cuisine including “pasta che finuocchi,” or pasta with wild fennel, “frascatole” (a kind of polenta made with chickpeas and peas) with bacon, and the tasty fava bean soup with lard.

Gallery:

CREDITS FOTO:

Pio Andrea Peri

Salvatore La Spina

Salvo La Spina

Fototonina

Parco Archeologico della Neapolis

Giornalista italiano con oltre 40 anni di esperienza nel mondo dei media.

Leggi in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano